Most countries around the world celebrate an Independence Day, commemorating the date of a country’s statehood. The stories and circumstances of independence vary from peaceful transitions to horrific wars. Mexico is no exception, and the story of Independence Day in Mexico is complex and intriguing.

The land that is now Mexico has been inhabited for thousands of years. Great civilizations have grown, thrived and ended during this time — from Mexico’s oldest known civilization, the Olmecs, to the last great pre-Hispanic civilization, the Aztecs. By 1519, Tenochtitlan, the capital of the Aztec Empire and site of modern-day Mexico City, was one of the largest cities in the world with more than 200,000 inhabitants.

Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés Credit: Wiki Commons

Thousands of years of history changed in a single day when, on April 22, 1519, Hernán Cortés set foot on the shores of “Mexico” near modern-day Veracruz. This day marks the beginning of the 300 years of Spanish rule in the land that would become Mexico.

Mexico, or New Spain as it was called at the time, became an important jewel in the Spanish crown. During the 16th and 17th centuries, Spain was the leading power in the world, elevated by the riches generated from precious metals, spices, textiles and other luxuries from its American colonies.

All of this wealth generated for the crown also created great affluence in New Spain. Yet this new prosperity in the colonies was centralized, benefiting only the top of a race-based societal hierarchy called the casta. Those born in Spain with fully Spanish blood reaped the greatest financial gains while the members of society who were indigenous, mixed-heritage, or even Spanish-born in New Spain (criollos) were considered of lower classes. Over time, this attitude did not sit well with these oppressed people.

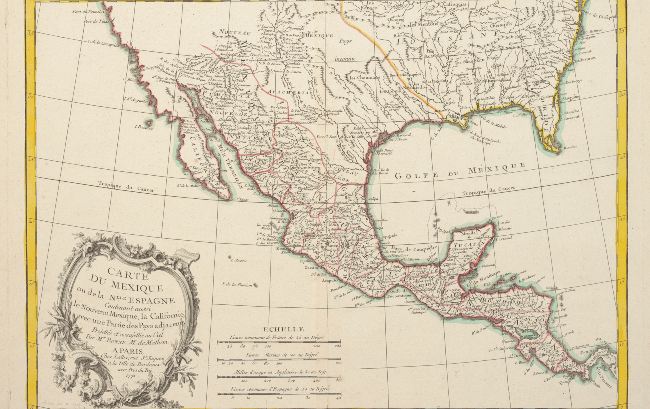

Map of New Spain created in 1771 Credit: Wiki Commons

Though uprisings took place over the years, none were successful in overturning Spanish rule. Yet the tides started to change with the destabilization of Spanish power in Europe. The growing Age of Enlightenment and Napoleon Bonaparte’s 1808 invasion of Spain opened the doors for new movements of independence in Spanish America, as the second-tier criollos and other lower classes felt discomfort and desired a redistribution of land, justice for the poor, and racial equality.

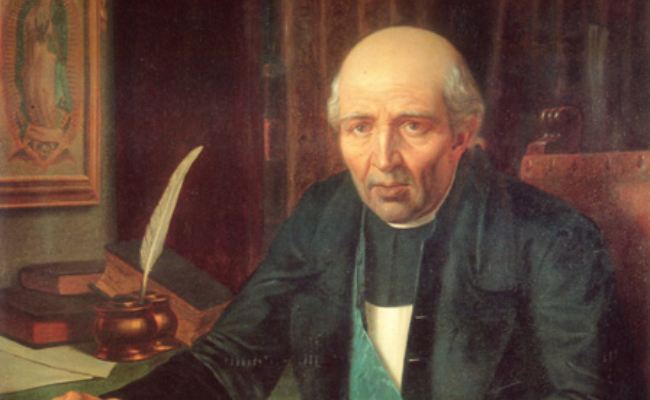

On September 16, 1810, a criollo priest named Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, who had been secretly planning a revolt, learned that his plot for revolution had been discovered. Before the Spanish could do anything to stop Hidalgo, he ran to a church in the city of Dolores, Guanajuato.

Father Hidalgo called on the people to revolt against the Spanish rule by any means. His famous speech, of which the exact words are unknown, became known as El Grito de Dolores (the Cry of Dolores). This speech inspired the people and began the final revolt against the Spanish rule, while Father Hidalgo came to be recognized as El Padre de la Patria (the Father of the Nation).

The Father of the Nation, Miguel Hidalgo Credit: Wiki Commons

Hidalgo went on to lead many successful revolts against the Spanish over the following year before being captured and killed in July 1811 at the age of 58. In Hidalgo’s absence, other leaders continued the fight. José María Morelos, also a priest and military general, lead the revolt until his capture and death in December 1815. From 1815 to 1821, most of the fighting was done by small bands of guerrilla fighters led by Guadalupe Victoria and Vicente Guerrero.

At this time, a colonel in the forces representing Spanish rule, Colonel Agustín de Iturbide, who had fought hard against the independence movement, made a bold move. Unsettled with a military coup back in Spain against the monarchy of Ferdinand VII and changes to Spain’s Constitution following the coup, Iturbide decided to support the revolt and fight for the independence of New Spain, joining forces with Guerrero and rebels across New Spain.

On August 24, 1821, representatives of the Spanish crown recognized the new nation as an independent state by signing the Treaty of Cordoba, coincidentally in Veracruz where Spanish colonization started with the landing of Cortes. On September 27, 1821, Iturbide’s army entered Mexico City; the following day, he claimed independence for the newly formed country and named it the Mexican Empire.

Independence Day in Mexico now

Today, Mexico celebrates its independence on September 16. Celebrations abound across the country with parades, festivals and a mass gathering in the central plaza in central Mexico City, to hear the President perform El Grito de Dolores, which goes:

| Spanish | English |

| ¡Mexicanos! ¡Vivan los héroes que nos dieron patria! ¡Viva Hidalgo! ¡Viva Morelos! ¡Viva Josefa Ortiz de Domínguez! ¡Viva Allende! ¡Viva Aldama y Matamoros! ¡Viva la Independencia Nacional! ¡Viva México! ¡Viva México! ¡Viva México! |

Mexicans! Long live the heroes who gave us our homeland! Long live Hidalgo! Long live Morelos! Long live Josefa Ortiz de Domínguez! Long live Allende! Long live Aldama and Matamoros! Long live the nation’s independence! Long Live Mexico! Long Live Mexico! Long Live Mexico! |

This is an incredible time to experience Mexico and its celebrations. If you are intrigued, contact Journey Mexico and let us put together a custom trip for you to experience this proud celebration in Mexico.

Read more: The Story of El Grito and Mexico’s Independence Day